Using Feature Flags To Fake The State Of External Systems

Most applications include code details to interact with external systems. Testing these interactions, especially in non-production systems, can be unpredictable. Feature flags provide a way to swap the real integration details with code that fakes different states of an external system. This avoids interruptions when those systems are offline, not responding as expected, or just hard to change.

Let’s imagine a Thermostat application that, among other things, determines if the outside temperature is between two values:

class Thermostat(private val temperatureService: TemperatureService) {

fun isBetween(minTemp: Int, maxTemp: Int): Boolean {

val currentTemp = temperatureService.get()

return currentTemp > minTemp && currentTemp < maxTemp

}

}

interface TemperatureService {

fun get(): Int

}

We could implement the TemperatureService with a version that calls a weather.gov URL and parses the response data:

class WeatherGovTemperatureService: TemperatureService {

override fun get() =

HourlyForecast.from("https://api.weather.gov/gridpoints/TOP/31,80/forecast/hourly")

.currentTemperature()

}

fun createBasicThermostatApp() = Thermostat(WeatherGovTemperatureService())

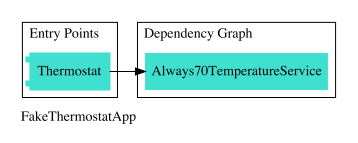

Or we could create a version that fakes a TemperatureService and always returns 70 degrees:

class Always70TemperatureService: TemperatureService {

override fun get() = 70

}

fun createFakeThermostatAppWithFakes() = Thermostat(Always70TemperatureService())

In either case, the Thermostat only depends on the TemperatureService interface and does not need to be changed to use different implementations. This concept is called dependency inversion and helps loosen the coupling between related objects in an application.

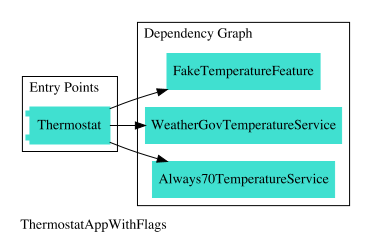

With two versions of TemperatureService, we can use a feature flag to control which version the app will use:

interface FakeTemperatureFeature {

val isEnabled : Boolean

}

fun createThermostatAppWithFlags(): Thermostat {

val feature =

object: FakeTemperatureFeature { override val isEnabled = true }

return Thermostat(

if (feature.isEnabled) Always70TemperatureService()

else WeatherGovTemperatureService()

)

}

Switching the state of FakeTemperatureFeature.isEnabled is now the only change needed to create a Thermostat with either version of the TemperatureService.

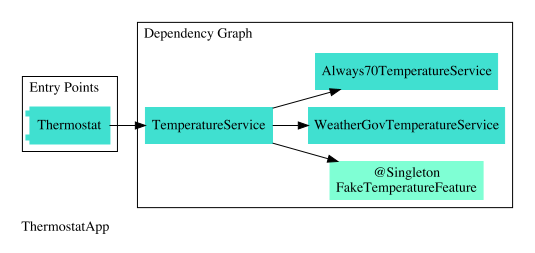

So far we have used simple factory functions to isolate the dependencies needed to create a Thermostat. But as the application grows in complexity, so can the the effort to manage these relationships. A dependency injection framework, like Dagger, can greatly reduce factory boilerplate and validate the object graph each time it is compiled:

@Module

class ThermostatModule {

@Provides fun thermostat(service: TemperatureService) = Thermostat(service)

@Provides fun nationalWeatherTempService() = WeatherGovTemperatureService()

@Provides fun always70TempService() = Always70TemperatureService()

@Provides @Singleton fun fakeTemperatureFeature() =

object: FakeTemperatureFeature { override val isEnabled = true }

@Provides fun temperatureService(

feature: FakeTemperatureFeature,

real: Provider<WeatherGovTemperatureService>,

fake: Provider<Always70TemperatureService>

) = if (feature.isEnabled) fake.get() else real.get()

}

@Component(modules = [ThermostatModule::class]) @Singleton

interface ThermostatApp {

fun thermostat(): Thermostat

}

fun createThermostatApp() = DaggerThermostatApp.create().thermostat()

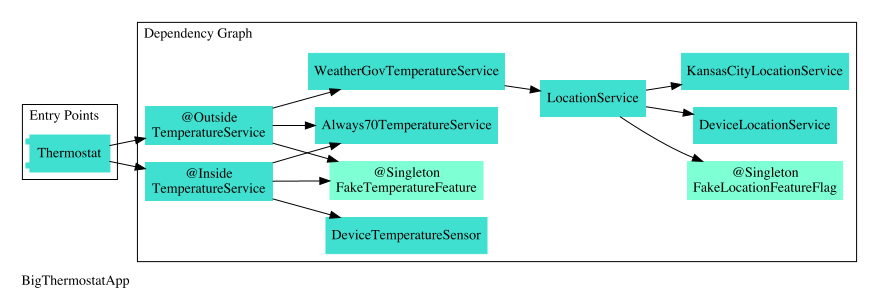

A future version of the dependency graph, with additional feature and flags, might look like this:

Finally, making features easy to switch can be useful in development, but we don’t want those changes to be accidentally released. We can prevent this with basic automated tests:

fun testThatFakeTemperatureFeatureIsFalse() {

val feature = ThermostatModule().fakeTemperatureFeature()

assert(!feature.isEnabled) {

"$feature.isEnabled should be false but was ${feature.isEnabled}"

}

}

To keep this example simple, the actual value of the flag is hardcoded object: FakeTemperatureFeature { override val isEnabled = true }. In certain situations it may be more useful to control the value from user interface so it can be switched without code changes. Still it’s unlikely you would want a feature that fakes external systems to be released to real users. Even if the flag is mutable in test builds, it should still be possible to write deterministic tests that prevent it’s release.

Summary

-

Invert dependencies on external details

-

Write a fake version (or use an existing test double) of the external details

-

Use a feature flag to declare which version to use

-

Isolate feature decisions in factories

-

Use injection to minimize creational boilerplate

-

Add automated tests to prevent releasing features accidentally

Additional Notes

This example focuses on how to make feature flag implementations safe and easy to maintain, but it leaves the actual value of the flag hardcoded in a factory function object: FakeTemperatureFeature { override val isEnabled = true }. In reality it may be more useful to control this from a user interface and store the value

Creating fake versions may seem like extra work, but if you’re writing unit tests, you may be able to feed two birds with one seed. In the example below, always60 or always70 could be repurposed in a fake temperature feature flag.

fun testThatIsBetweenReturnsExpectedValues() {

val always60 = object: TemperatureService { override fun get() = 60 }

val always70 = object: TemperatureService { override fun get() = 70 }

val minTemp = 68

val maxTemp = 72

assert(Thermostat(always60).isBetween(minTemp, maxTemp) == false)

assert(Thermostat(always70).isBetween(minTemp, maxTemp) == true)

}

You don’t need to make all integrations flaggable from the start. The next time you’re blocked by problems with an outside system, try applying a flag for just the calls needed to unblock your current task. It should be possible to get part of an application working with object fakes even if the rest is not.

FakeTemperatureFlag.isEnabled has a boolean type because only two value states were necessary: true & false (feature flags with only two states are often called feature toggles). But there are situations where flags with more than two states may be suitable. We might want to test with a set of fakes that all throw errors and a set of fakes that all return stubbed values. A flag for this might have three states: real, stubs, and errors.